Category Archives: Scholar/Scholarship

RETIREMENT? HUH?!

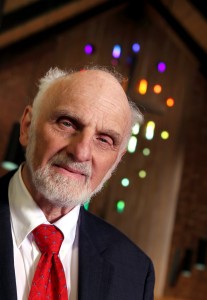

Walter Brueggemann is one of the greatest living biblical scholars. I don’t always agree with him, but he always makes me think.

Check this out at www.walterbrueggemann.com: He wrote 53 books by the typical retirement age of 65 and another 78 books from age 65 to now at 86 on this his birthday!

MARY BEARD: HAPPY SCHOLAR AND TROUBLEMAKER

I am grateful for John Fea recommending this piece on the inimitable, Mary Beard:

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jan/30/mary-beard-the-cult-of

A few sections I culled:

She is not afraid to take apart her own work: at that same conference in the early 1990s, she presented a paper that repudiated one of the scholarly articles that had helped make her name a decade earlier, an influential study of Rome’s Vestal Virgins. It was an extremely unusual thing for a scholar to do. “She doesn’t let herself off – she’s not one of those scholars who is building an unassailable monument of work to leave behind her,” Woolf said. “She is quite happy to go back to her earlier self and say, ‘Nah.’”

When I asked her if she would countenance taking Isis’s ideology seriously, she said: “That’s the wrong question. There is no argument that I won’t take seriously. Thinking through how you look to your enemies is helpful. That doesn’t mean that your ideology is wrong and theirs is right, but maybe you have to recognise that they have one – and that it may be logically coherent. Which may be uncomfortable.”

SCHOLARLY LANGUAGE

Carl Trueman is always worth reading. Here he reflects on some (many?) scholars penchant to write gibberish:

Years ago, while I was on faculty at the University of Nottingham, a colleague and I used to play a game with the students. We would give them a quiz consisting of paragraphs drawn from great theologians and philosophers, which they had to attribute. In every quiz we included one paragraph of complete gibberish, which we had made up ourselves over a pint of beer in the faculty club. Words such as “alterity,” “the Other,” and “subjectification” abounded, along with nouns used as verbs and a plethora of hyphenated neologisms and random capitalizations. The students never failed to attempt some kind of attribution (Paul Tillich, I think, was usually the most popular) and to profess admiration for the depth of thought and insight contained in the paragraph.

The rest is here: https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2017/06/reflections-on-being-the-dumbest-man-in-the-room

PRINCETON LOG #3: PEOPLE

The past two posts on Princeton have focused on places. This one focuses on people. My last week Princeton included four wonderful days with some terrific folk. My first was with well-known artist and author, Makoto Fujimura or Mako for short. Mako has recently written an absorbing book called Silence and Beauty. It is a commentary of sorts on Shusaku Endo’s novel, Silence.

We took a day trip to Yale. There we met with David and Karen Mahan. Doreen worked with Dave at Virginia Tech in the early 1980s. Both of them were on staff with Campus Crusade for Christ (Cru). I met Dave during the summer of 1985. Our son, Chris, is looking into various graduate programs. Yale is one of his possibilities so it was wonderful that he could join us.

James McPherson is widely hailed as our greatest living historian of the Civil War. In 1989 he won the Pulitzer Prize for his magisterial book, Battle Cry of Freedom. I spoke with Professor McPherson on how various people processed the carnage of the war.

My week finished up with Carl Trueman, Professor of Church History at Westminster Theological Seminary. Carl and I have corresponded via email, but never met in person. He is a terrific historian and wonderful essayist. Make sure to check him out on First Things and Mortification of Spin.

PRINCETON LOG #2: WHAT WE’RE STUDYING (AND A NOTE ON PURGATORY)

Yesterday, we posted a picture outside of Payne Hall. Here is our living room:

Here is the huge balcony we share with one other apartment:

Princeton is a walking town, so we (gladly) do lots of it everyday. A few pictures of our walk with a couple of the University which is right across the street from the quaint town.

Some spots along our daily walk to the library:

You may have heard me mock pastors who say they are “married to the most beautiful woman in the world.” I like to jest that she must be getting very tired. Well, I think it is fair to say that the day the following picture was shot I could safely say I was married to the most beautiful woman in the library.

Doreen had no idea I was taking a picture, but now she will be on to me. She is doing research on Sarah Edwards, wife of Jonathan. As many of you know, her first book covers the marriage of Jonathan and Sarah, along with the Whitefields and Wesleys. I happy to say that the Princeton library carries her book along with two of mine.

The burial place of Jonathan and Sarah Edwards. Also, the graveyard for John Witherspoon, Aaron Burr, and many more.

My spot in the library:

I am finishing up a thirty-five year study of how to trust God in the midst of suffering. One of my final reads is Ralph Wood’s utterly amazing book on Flannery O’Connor. At my current pace, this 280 page book will have over 500 marginal notes. It is one of the most insightful and beautifully written books I’ve ever read. If you choose to read it, go very slow and bring out your pen!

Protestants don’t tend to believe in Purgatory. I have joked that looking at someone’s photos of their family vacation can feel like Purgatory exists. Hopefully, you will find this log more celestial in nature.

PRINCETON LOG #1: GETTING THERE

Packed and ready to go:

Dinner (and spent the night) with wonderful friends, Bill and Helen. A great restaurant Bill and Helen introduced us to:

SLAIN BY GOD

Timothy Larsen is McManis Professor of Christian Thought at Wheaton College. He’s been a Visiting Fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge. Some of the research for this new book was conducted while a Visiting Fellow at All Souls College, Oxford.

This interview revolves around Larsen’s latest book, The Slain God: Anthropologists and the Christian Faith http://www.amazon.com/Slain-God-Anthropologists-Christian-Faith/dp/0199657874

Moore: This is a rather unusual area of study. What led you to write an entire book on it?

Larsen: My whole scholarly life I have been interested in the collision between modern thought and historic, orthodox, Christian beliefs. A lot of these tensions have been explored over and over and over again by scholars: Christianity and Darwinism, Christianity and Marxism, Christianity and Freudian theories, Christianity and modern biblical criticism, and so on and on. When I read the letters and self-reflections of people in the second half of the nineteenth century and the twentieth century, however, what I noticed repeatedly was them mentioning the writings of anthropologists as unsettling to faith. This was a major theme in the primary sources, in the historical record. What had anthropologists discovered or theorized that seemed incompatible with Christian thought? I wondered. When I tried to find a written explanation for this, I instead learned that no scholar had made a sustained attempt to try to map this terrain as of yet, so I decided I would have a go at it myself.

Moore: When does the discipline of anthropology as we think of it today begin?

Larsen: In the second half of the nineteenth century. E. B. Tylor, who is often considered the founder of the discipline, published an early seminal work, Primitive Culture, in 1871, and was appointed to the first university position in anthropology (at the University of Oxford) in 1884. Franz Boaz, who is considered the founder of the discipline in the United States, received his first university appointment in 1899 (at Columbia University). During the World War I era, Bronislaw Malinowski pioneered the expectation of intensive fieldwork.

Moore: You write that Edward Tylor “could not find a way to think anthropologically and as a Christian at the same time.” Why is that? What would you have told him if you had the chance?

Larsen: He was in the grip of a pretty smug, self-flattering, stadial way of thinking – with the three stages of human development being: savages, then barbarians, and then civilized people. He thought because “primitive” peoples were religious this somehow discredited faith as incompatible with being modern and civilized and scientific and so on.

I wish I could have explained to him that there is a lot more continuity in the human condition over time than he ever imagined – that so-called “savage” people were actually quite logical, scientific, and rational in ways he could not see, and that so-called modern people have other needs and thoughts and experiences and insights that do not fit into his procrustean assumptions about what is means to be a rationalistic, scientific, modern person.

Moore: The Christians at the college in Didsbury had a wonderful confidence that made them more than willing to engage skeptics like James George Frazer. How common was that among the Christian population during the late nineteenth century?

Larsen: What a great question!

This is one of the major misconceptions of evangelical and orthodox Christians in the nineteenth century – that they were somehow fearful of modern ideas and rejecting scientific and theoretical advances, that they were hostile and obscurantist. Some of that stereotype is just erroneous secularist propaganda and urban legends that have been transmuted into the public consciousness as “fact”. For example, you can read in major, premier, authoritative venues (a recent book by Yale University Press, for example, and articles in papers of record such as the New York Times) that Christians in the nineteenth century opposed the introduction of anesthetics for women in childbirth because Genesis supposedly dictates that this experience must be painful. Yet this is a completely false urban legend.

I defy anyone to find a single sermon by any minster of any denomination anywhere saying any such thing, let alone an article in a Christian magazine or other publication, let alone an official pronouncement by a denomination. There are many examples of this kind of thing.

Some of this misunderstanding comes from back-dating things that happened in the Fundamentalist movement beginning in the 1920s (which did have anti-intellectual, fearful, and obscurantist elements to it).

Late Victorian Christianity was actually quite open to and welcoming of new knowledge and scientific theories—even ones that were surprising given traditional Christian assumptions—and very confident that faith and science would cohere together in one, integrated worldview.

Moore: Mary Douglas is an utterly fascinating person. She was shrewd in the best sense of that word. Unpack her observation that “Debates which originate in quite mundane issues tend to become religious if they go on long enough.”

Larsen: Yes, yes, I feel like I have been inspired to become a better, braver scholar by reading about her life and work. She was so comfortable in her own skin as a leading intellectual who was also a conservative Christian! That particular quote has been picked up on by several anthropologists since I wrote the book and it haunts me as well.

What she means is that people who imagine that theology can be set aside, marginalized, or ignored in modern academic discussions are actually the ones being intellectually naïve. What intellectuals really care about are issues which go to the heart of the question of the nature of reality, of meaning, of ethics, of values – and these are all debates that are inherently bound up with theological content and reflections. Whenever you discuss anything (“Is it important to recycle plastics?” let’s say, “Or should I buy this new suit of clothes that I want?”), the more you discuss it without coming to a quick conclusion, the two sides of the question inevitably lead you back to a more fundamental value or sense of meaning or conviction or principle or proposition and this is heading you into the territory of religion.

Moore: What has been the response to your book from those within the academic world of anthropology?

Larsen: I am unbelievably, joyfully, relieved to say that it has been received very well. I say this because for at least a couple years while I was researching it I felt like an incompetent interloper, if not a complete fraud. I have never even taken an Anthropology 101 course! I had to learn the whole discipline from scratch just by reading, and reading, and reading. I was quite ready to be rebuked by professional anthropologists for not understanding the key theories in the discipline correctly and just not “getting it”. Instead, the contemporary anthropologists that I most admired, not least the ones who do not self-identify as Christians – including Tanya Luhrmann at Stanford University and Joel Robbins at Cambridge University, as well as the former Director of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Jonathan Benthall (in the Times Literary Supplement! – I would count it a triumph to have my work abused in the TLS) – have received it so wonderfully warmly and appreciatively. There was a whole panel on the book at the annual meeting the American Anthropological Association, and I have been invited to speak on it at the major anthropology seminar at Oxford, at the London School of Economics (the very storied seminar that Malinowski founded), at Cambridge, at Northwestern University, and so on. It feels like dumb luck that I wrote this book at a time when the Anthropology of Christianity has suddenly become a hot subfield in the discipline. I am very, very grateful for how anthropologists have welcomed and received my work.

Moore: What kind of non-academic would profit from reading your book?

Larsen: Another surprisingly wonderful question. These things are a matter of taste, so I am willing to accept humbly if others see it differently, but I see myself as a narrative historian who works very hard to have a literary quality in my work akin to an author of fiction. Just like a short story writer uses a lot of details in description to build up a vivid, compelling portrait of an imagined character, so I have tried to do that with these historical characters. In other words, I think the lives I present in the book do work for the ordinary, intellectually curious reader who cares about the human condition and experience as lived up-close and in-detail. Buy it for your grandmother for Christmas!

THE PRACTICALITY OF SOUND SCHOLARSHIP

If you ever wondered about the impact of a scholar, read this truly arresting and encouraging article:

http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2014/january-february/world-missionaries-made.html