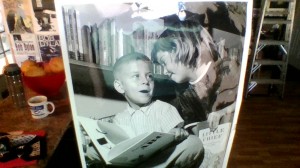

Reading to my sister Lisa during the opening of our neighborhood library. By the way, in case you have not heard of it, a library is a place that has a lot of books where people can borrow them…

Monthly Archives: March 2016

WRITE IN YOUR BIBLE

If Jonathan Edwards went to these lengths, what should we do?

http://www.bibledesignblog.com/2015/05/jonathan-edwards-blank-bible-guest-post-matthew-everhard.html

DISAPPEARING CHURCH

My interview with author and Aussie pastor, Mark Sayers:

Moore: You’ve been addressing some of these themes in previous books, so what led you to write a full-throated account?

Sayers: I was driven by a conviction that something radical was changing culturally, and that the Church was struggling to not just catch up but articulate this shift. For decades now the Church has relied on the strategy of cultural relevance to engage Western culture. The premise of this strategy was based on two great assumptions. First, that Western culture had entered a kind of post-Christian phase, and second that the best way to engage this post-Christian phase was through employing strategies and tactics learned on the mission field with pre-Christian cultures.

This was the strategy that ultimately created the contemporary church movement. I am not suggesting that the strategy of cultural relevance has not been fruitful nor that we should abandon it. The strategy of cultural relevance works well in pre-Christian or traditional cultures where the gospel can be communicated into and built around local symbols, stories, traditions, conventions and structures. However, the mood behind the post-Christian culture of the West ultimately seeks to deconstruct and contest all symbols, stories, traditions, conventions and structures. How do you apply a strategy of cultural relevance in a Western context which liquifies culture? Missiology emerged as a way of engaging non-Western traditional cultures without colonizing them. In our post-traditional West, the danger is that when the church engages the cultural solely with the strategy of cultural relevance, too often the church is colonized by the post-Christian mood. I am suggesting that alongside the strategy of relevance we need a strategy of resilience. Not retreat, but cultural engagement with robust resilience.

Moore: In an early section titled “The Soft Power of Post-Christianity” my marginal note reads: “Well put and insightful. We get dulled, duped, and diverted by the panoply of options that indirectly say Christianity is irrelevant.” Describe a bit of the allure and toxic nature of our current cultural moment.

Sayers: Post-Christianity is ultimately the project of the West to move beyond Christianity, whilst feasting upon its fruit. Thus it constantly offers us options and off ramps, in which we seemingly have what we enjoy about faith, but without the sacrifices and commitments. It does not demand that we become apostates rather that we reshape our faith to suit the contours of the day, and in the process offers us the promise of tangible freedoms and pleasures for doing so. It does not challenge our faith head on in a kind of apologetics debate; rather it uses soft power, offering a continual background hum of options and incentives which eat away at our commitments. We are offered the mirage that we can have community without commitment, faith without discipleship, the kingdom without the King. To steal and misquote Eliot’s line, our faith doesn’t disappear with a bang but with a whimper.

Moore: Much of modern culture seems rather benign. We all benefit from breakthroughs in technology, medicine and so much more. It seems a bit ungrateful to level harsh criticisms (something you don’t do) against a culture that produced such benefits. How can the church be winsome in its critique without losing fidelity to the biblical story?

Sayers: Its key that we remember that human culture reflects human nature, thus it mirrors the reality that we are both created and loved, yet also fallen. It is also important to remember that culture is not a monolith, but contains all kinds of spheres, such as media, law, art, and politics. In a globalized world, locations also still matters. So we need nuanced, wise and discerning cultural critique. Scripture shows us that such wisdom and discernment flows from a close abiding with Christ.

Moore: The following is a generality, but does, I believe, depict a big problem. In America, older evangelicals can be faulted with tethering the gospel to certain political agendas that have little or nothing to do with the gospel. Younger evangelicals have reacted in the opposite direction with a disinclination to say much about certain issues that the gospel does address. Do you have a similar challenge in Australia?

Sayers: Traditionally evangelicalism is more politically diverse in Australia than in the US. Having said that, with the rise of the Internet, increasingly Australian evangelicals and even some elements of the media, confuse our relatively small local evangelicalism with American political conservatism. So we also have had understandable move away from some of the compromises with right wing politics, but sometimes the reaction slides into an equally concerning compromise with left wing politics.

This is all happening at a time, where across the Western world we are seeing the rise of a harder left and a harder right. This comes as a shock for since the fall of the Berlin Wall, with Bill Clinton and Tony Blair moving politics into the center, it seemed that such ideology had had its day. Yet ideology is back. What I find fascinating though is behind this move to further edges of the right and left is a common thread. Both espouse a kind of anti-institutional impulse which seeks to remove the restraints on the individual will. Both seek to either return to an idealized past or a utopian future through the hand of a kind of a benevolent, paternal entity be it government, tech companies, or the global financial market. Both end up ignoring, or bypassing the mediating institutions such as family, neighborhood, community organizations or church. Thus, creating the contemporary, atomized, and commitment phobic self, dizzy with choice. There is a significant and growing missional opportunity here for the church to inhabit and rehabilitate this ignored space.

Moore: You write about “creative minorities.” In what ways can the church better remember both words of that description?

Sayers: Writers from Arnold Toynbee to Malcolm Gladwell have shown the way that creativity emerges so often from the margins. This is true in politics, culture, art and religion. The marginal position, isolating one from the mainstream, enables one to view the mainstream from the outside. To in a sense be a part, but also to stand apart and see the idols flaws, and myths of the mainstream culture. To be invited to be a healing presence with good news that directly addresses those idols, flaws and myths. However, as the story of both Israel, and Christ shows us, the margins at best are not comfortable and at worse harm and hurt. To be a true creative minority, the church must truly understand that we will always be mocked, persecuted, and marginalized, and yet we must meet such a response with love and faithfulness. Such a posture provides a fruitful creative tension.

Moore: What are a few goals you would like your readers to walk away with from having read Disappearing Church?

Sayers: There is no going back. We will most likely live the entirety of our lives in an increasingly diverse, contested, globalized, and divided world. As William Davidow and Moises Naim have shown, this world will also be a fragile one. Thus such a moment will be served by a church that is relevant by being resilient. With change and chaos as the norm, a nostalgic desire to return to halcyon days is deeply tempting. Instead of wanting to return to the past, we must learn from the past. Two thousand years of Church history have shown us that again and again, even as large portions of the Church compromise with the spirit of the day. Creative minorities, who engaged new landscapes with creativity alongside biblical orthodoxy and faithfulness, flourish, bring good news and live as ambassadors of the kingdom. This can and will again happen in our day. If in some tiny way Disappearing Church can contribute to that renaissance I will be deeply grateful to Him.

SEMINARY…A CAUTIONARY TALE

This short reflection comes after I read about an abusive husband who was theologically trained and a pastor.

I am a graduate of both Dallas Theological Seminary and Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Both were formative in my spiritual development.

One concern for me is how easy it is to be accepted as a student at all evangelical seminaries. Being “called” is almost always an individual affair. That is, one describes to the prospective seminary their fitness to minister based solely on one’s own assessment. Disastrous stuff. Seminaries must do much better here.

Some dear friends were made in seminary, both in Dallas and at Trinity. However, I met my fair share of folks at both places who raised serious concerns about their fitness for ministry.

NO LONGER IN KANSAS

Some early reflections from a new course/writing project:

There are three things I’ve noticed about Christians who keep growing: They are teachable (you could say humble), pain has caused them to wrestle more honestly with the Christian faith, and they are curious/hopeful that there is much more to the Christian faith than what they presently experience.

To those of us in teaching positions we must have these qualities as well. Dr. Howard Hendricks liked to say, “You can’t impart what you don’t possess.” And Dr. Luke wrote, “A pupil is not above his teacher; but everyone, after he has been fully trained, will be like his teacher.” (Luke 6:40) Do you want people to embody the same virtues which characterize your life?

Those of us who teach need to work hard at saying things clearly and in ways that fire the imagination. Thomas Paine’s approach in Common Sense reminds us of the former, while writers like Chesterton and Lewis help with the latter.